Nicholas Smith

*1964, Stockholm. Philosopher, lecturer in philosophy at Södertörn University; works in the research project "Perceptions of the Other: Aesthetics, Ethics and Prejudice" at Södertörn University.

Full CV (Click here)

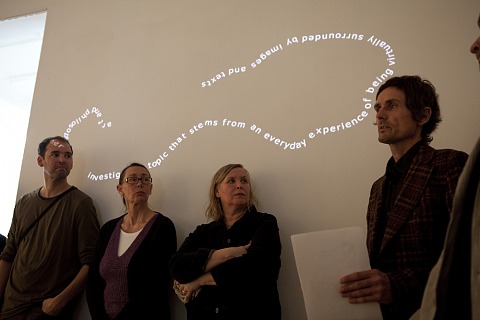

TotalRecall - being surrounded by images and texts

“Insofar as we live in a culture whose technological advances abet the production and dissemination of such images at a hitherto unimagined level, it is necessary to focus on how they work and what they do, rather than move past them too quickly to the ideas they represent or the reality they purport to depict” (Martin Jay).[1]

A part of our new predicament, or what may perhaps be called a condition, seems to find expression in a new alloy of emotions and technology. There is an increasing feeling of being constantly submerged in never ending receptions and relays of images and text messages. There is also and at the same time a feeling of extreme rapidity in these processes, which border on re-presentation being simultaneous with the event (digital transmission of live-broadcast). New technology, it seems, alters our traditional conceptions of two central notions, namely our conception of the event and its reproduction. This process is in part well documented in media- and technology studies, urban anthropology and sociology etc. But the philosophical consequences of this condition has proved difficult to fathom, not only because of its happening here and now, and the rapidity whereby new technology is introduced. There are, I will argue, aspects of this that need translation into other contexts (such as art, thinking and poetry) in order to be understood. Technology by itself, for instance, is clearly not the place from which to reflect on these processes. A hypothesis here is that this predicament or condition must correspond to a new ‘transcendental aesthetics’ since the processes alluded to effect our most fundamental categories of understanding, which since Kant have been determined as time and space, outlined in his Critique of Pure Reason. To put the question in as naïve a form as is possible, one can ask: What time is it on the internet? What is the internet and where is it? Even though there are perfectly good technical answers to these simple questions, these will have little to do with our understanding of what is really happening.

We are both subjected to this onslaught of images and texts, and actively support it by contributing to its dissemination (both professionally and in our personal lives). But who are “we” here, what is the community that is at stake? Are we speaking only as passive consumers of capitalist merchandise we have no real option to turn away from? Or is it a community of ‘citizens’, with the power and obligation to act politically in (what can here, for the sake of brevity, be called) democratic systems? More to the point: does this new experience only arise for those who participate in the techno-scientific communal ‘world’? As a first answer I think one must say yes, there is a restriction and a locality operative here, but one that does not function according to the traditional binaries of rich/poor, developed/underdeveloped, North/South, colonial/colonized etc. For the effects of this new time and space is also in a sense “global” and reach into the remote, poor and underdeveloped parts of the world. What is this ‘locality’? It is closely tied to virtuality in the sense of atopic technology and capitalist marketing strategies on the one hand, but equally so to liberatory and perhaps even revolutionary politics that are always bound to a place, a specific culture.

Our culture today – restricting the scope here to Western culture (as if that was something that could be done) – is predominantly visual. In a certain sense, this is no news. As many have pointed out, ever since the Platonic determination of thinking in its highest form as theoria, i.e. a ‘seeing’ of ideas or forms, the emphasis on visual activities and metaphors have come to dominate Western culture. In Plato’s work Timaeus, the genesis of sight is compared to that of reason and intellect, whereas the genesis of the other senses such as touching and smelling is relegated to the lower, material parts of the body. With the ‘mind’s eye’, we can perceive the highest, transcendent being of the forms or ideas, which later Christian philosophers adopted to the possibility to ‘see’ God, a notion that was reinforced during the renaissance with thinkers such as Ficino (who translated Plato into Latin). Vision was then dubbed ‘the noblest of the senses’ by philosophers such as Descartes and Thomas Reid in the 17th and 18th century.[2]

What is at stake is the question of what role the contemporary culture of notably digital images and texts that centres around what used to be called the Internet 2.0, plays in this scheme. It may seem far-fetched to hypothesize that there could be any more significant links between the metaphysics of optics in the history of philosophy and posting low-resolution video clips on YouTube, but this is nevertheless an idea that is investigated in the project. What could make such a hypothesis more plausible? First of all, stretching credibility somewhat, there is the historical connection between precisely Platonism which can be seen as an interconnection between non-sensuous forms and the WorldWideWeb. Internet can be seen as a kind of ‘materialization’, in similarly non-sensuous cyberspace, of ideas that must be historically connected to Platonism via the natural-scientific revolution initiated by Galilei, Descartes and Newton in the 17th century. A central aspect of this new determination of the world is that the whole world becomes calculable, it is as if a web of ideas (mathematical, physical) were cast over the world achieving a non-religious sense of unity that had never occurred previously. The threads of the mathematico-physical project here for the first time achieve a universality that is non-negotiable.[3] This is the beginning of the internet in a sense, the seed from which it sprang.

In an important text, written in exile from Nazi persecution in Paris in the mid 1930’s, Walter Benjamin argues that artworks not only reflect the surrounding world in which they were made, but that they also contribute in transforming our perception:

Just as the entire mode of existence of human collectives changes over long historical periods, so too does their mode of perception. The way in which human perception is organized – the medium in which it occurs – is conditioned not only by nature but by history. The era of the migration of peoples, an era which saw the rise of the late-Roman art industry and the Vienna Genesis, developed not only an art different from that of antiquity but also a different perception [sondern auch eine andere Wahrnehmung].[4]

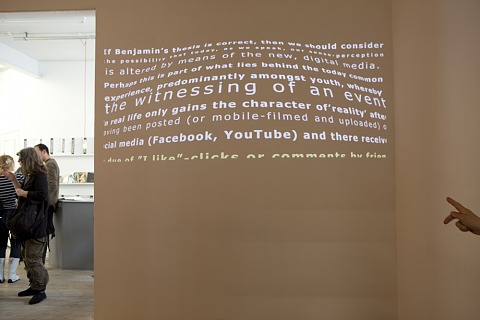

If Benjamin’s thesis is correct, then we should consider the possibility that today, as we speak, our sense perception is altered by means of the new, digital media. Perhaps this is part of what lies behind the today common experience, predominantly amongst youth, whereby the witnessing of an event in real life only gains the character of ‘reality’ after having been posted (or mobile-filmed and uploaded) on social media (Facebook, YouTube) and there received its due of “I like”-clicks or comments by friends. What the eye sees is not registered as ‘real’ in the intersubjective sense (where we can agree that this happened, and had the character of event) until it has been medialized, presented on the internet and been acknowledged by peers. This is what makes reality today. In a certain sense, this has always been the case: practically speaking, we always communicate in a dialectic of saying and response so that what is said awaits the confirmation or negation by the other. The ‘press click if you like’-culture prevalent on Facebook would only supervene on already active structures of social communication, and in that sense merely make more visible what has already been going on for a long time.

In her essay “Plato’s cave”, Susan Sontag speaks of the ‘shock’ that photographs can bring with them when they show something new. The example she discusses is her own experience as a twelve-year old when she for the first time saw photos of Bergen-Belsen and Dachau by chance in a bookstore in Santa Monica in 1945. At that time, it was possible to be a “horror virgin” she explains in a later interview, but the proliferation of images in the following decades has, according to Sontag, effectively rendered this impossible. In the essay, she says that her life was divided into a before and after having seen the photographs, and she describes the event in inverted theological terms saying that it was a “negative epiphany”, the “prototypically modern revelation”.[5] In the interview from 1979, Sontag explains further:

I think that that experience was perhaps only possible at that time, or a few years after. Today that sort of material impinges on people very early – through television, say – so that it would not be possible for anyone growing up later than the 1940's to be a horror virgin and to see atrocious, appalling images for the first time at the age of twelve. That was before television, and when newspapers would print only very discreet photographs. As far as what died – right then I understood that there is evil in nature.[6]

For us today, as Sontag I think rightly suggests, this relation between image and feeling no longer seems possible. In fact, the relation between image and experience seems to be a precise inversion of what she describes: prior to reflection and knowledge about historical facts, we are immersed in images of them. This signals a shift in how we conceive of not only our relation to singular images, but more decisively about what experience is and also about the ontology of the image. As Deleuze puts it, it is not that we are surrounded by images so much, for we are not: what surrounds is clichés, and the problem is instead the difficult encounter with a wholly different type of images: that is to say, tearing real images from clichés. [7] This is what lies behind the work done and presented in this exhibition. Just to point out two extremes in the variety of working methods: There are images ‘directly’ from nature, impressions that via the manual sketchbook are reconstructed on the wall in an attempt to reappropriate the historically laden tradition of landscape painting (Egli). There are also images that have not been selected by the artist at all, but that stem from a non-algorithmic random generator (based on atmospheric noise), which has ‘selected’ images in a completely arbitrary fashion from the internet’s infinity of images (Pils). In both cases, the images procured then serve as mere material to be worked on artistically, and it is the transformations that occur in this process that ‘makes’ the artwork.

Nicholas Smith

[1] See M. Smith (ed.), Visual Culture Studies. Interviews with Key Thinkers, (London: Sage, 2008) p. 182f.

[2] For general treatments of this issue, see Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1979); Martin Jay, Downcast Eyes: the Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought (University of California Press, 1994).

[3] See the analyses of Alexandre Koyré, Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger for instance.

[4] Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, Jennings, Doherty & Levin (ed.s), (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2008), p. 23. The German text is in: Gesammelte Schriften Bd. 2, p. 439.

[5] Susan Sontag, ”Plato’s cave” in On Photography [1973], electronic edition: 2005 by RosettaBooks LLC, New York, p. 14f.

[6] ”Sontag Talking”, interview with Charles Simmons, December 18, 1977 in The New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/1977/12/18/books/booksspecial/sontag-talking.html

[7] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2. The Time-Image, tr. H. Tomlinson & R. Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), p. 20ff.

| Preview | Attachment | Size |

|---|---|---|

| CV | 122.25 KB |